U.S. Court Rules on Exclusions to Aerial Spraying Claim

On August 11, 2025, a federal district court in New York issued an opinion in the matter of Whitlock Air Service, Inc. v. National Union Fire Insurance Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa., 2025 WL 2302324 (S.D.N.Y. 2025), illustrating the dispositive effect of well-defined exclusions in insurance policies issued in specialized industries like aerial application.

Background Facts

The case involved the activities of Whitlock Air Service, a Texas-based company that provided aerial application and vegetation management services for municipalities and utility districts in the state. It was subcontracted to apply herbicides as part of the Bois D’Arc Lake Dam Project near Honey Grove, Texas, in May 2022.

Whitlock performed three applications of fertilizer and herbicide in late 2021, and again in May 2022. On that last occasion, Whitlock personnel mixed and loaded the herbicides Oust and OpenSight onto one of its aircraft and gave its contract pilot instructions about the work to be done. The pilot performed the aerial application using Whitlock’s aircraft.

About a week later, the project’s prime contractor, Phillips & Jordan (P&J”), alleged that the application caused damage across 170 acres (well more than the 94.6 acres sprayed), including vegetation loss, erosion, and soil accumulation. P&J sued Whitlock in federal court on claims of breach of contract and negligence, seeking $2.45 million in damages, consisting primarily of expenses incurred in remediating the project.

Policies at Issue

At the time of the May 2022 aerial application, Whitlock was insured under two policies issued by National Union Fire Insurance Company (“NUFIC”). The first, an Aerial Applicator Aircraft Policy, provided $1 million in “non-chemical” liability coverage and $300,000 in “chemical” liability coverage. The second, an Aviation Commercial General Liability (ACGL) Policy, carried a $5 million per-occurrence limit. NUFIC agreed to defend Whitlock under the Aerial Applicator Policy, subject to a reservation of rights, but denied coverage under the ACGL Policy, citing several exclusions. Whitlock brought suit seeking a declaration of coverage and damages for breach of contract.

The parties agreed that, unless an exclusion applied, coverage existed for the alleged damage because the aerial application constituted an “occurrence” during the policy period. The case then turned on the issue of whether the insurer had carried its burden to show that an exclusion clearly applied.

NUFIC Policy: Ambiguity vs. But For Causation

With respect to the Aerial Applicator Policy, the key provision was Exclusion 7(b), which barred coverage for property damage “arising from direct aerial application.” Under Texas law, the phrases “arising out of” and “arising from” denote simple but-for causation, as opposed to proximate causation. The ariel applicator, Whitlock, did not dispute that the property damage alleged could not have occurred but for its aerial application in May 2022. Therefore, the court rule, because Exclusion 7(b) straightforwardly excluded coverage for property damage “arising from direct aerial application” and Whitlock was not entitled to coverage under the Aerial Applicator Policy.

Whitlock nevertheless argued the exclusion was ambiguous in that it excluded coverage for risks “at the heart” of the policy, namely “property damage caused by an aerial applicator’s use of chemicals.” The court rejected this argument, noting the absence of any legal authority for the proposition that exclusions that are closely related to the scope of coverage (or to an insured’s alleged intent in purchasing a policy) are ambiguous as a matter of law.

The court also decided that the aerial applicator mischaracterized the relationship between the relevant exclusion and the grant of coverage applicable generically to property damage “arising out of the ownership, maintenance, or use of the aircraft,” where such property damage could occur in numerous settings other than aerial application. For instance, coverage would be available to if an insured aircraft were to collide with and thereby damage property owned by someone else, either on the ground or in the air. The policy’s liability coverage thus extended broadly to damages arising from the ownership, maintenance, or use of the aircraft, and aerial spraying was only one subset of such risks. Because the alleged damage would not have occurred but for the spraying, the exclusion applied.

The aerial applicator also argued that Exclusion 7(b)’s use of the adjective “direct,” as in the phrase “direct aerial application,” was ambiguous because the policy did not define “direct,” and NUFIC relied on a dictionary that defined “direct” to mean “to point, extend, or project in a specified line or course.” As such, the property damage at issue extended beyond the approximately 94.6 acres that the aerial applicator’s pilot “sprayed directly” meaning that that Exclusion 7(b), which the court must “strictly construe” against NUFIC, did not preclude coverage for at least the approximately 75.6 acres that Whitlock’s pilot did not directly spray.

The court rejected this, however, because the aerial applicator failed to point to any possible cause of the damage alleged other than its aerial application, and even though the aerial applicator’s pilot did not directly spray the entire area that was damaged, but there was no dispute that the admittedly “direct” application that the pilot did perform on a sizeable portion of that area was a but-for cause of all the damage.

Aviation Commercial General Liability Policy

The ACGL Policy issued by NUFIC provided coverage to the aerial applicator, Whitlock, for damages it became legally obligated to pay due to “bodily injury” or “property damage” resulting from its “aviation operations.” These operations were broadly defined to include not only the ownership, maintenance, and use of locations for aviation activities, but also any activities incidental or necessary to aviation work. On its face, this insuring agreement appeared to cover the claims asserted in the underlying lawsuit, unless a policy exclusion applied, however several exclusions were central to the parties’ dispute:

- Exclusion 2.g denied coverage for injury or damage arising out of the ownership, maintenance, or use of any aircraft owned, operated, rented, or loaned to the insured.

- Exclusions 2.j(5) and 2.j(6) removed coverage for property damage tied directly to ongoing operations on specific property or to repair work incorrectly performed.

- Additionally, Endorsement No. 2 eliminated coverage for property damage that fell within the “Products-Completed Operations Hazard,” which applied to damage occurring away from the insured’s premises and arising from completed work.

NUFIC argued that each of these exclusions, particularly Exclusion 2.g, barred coverage for the claims in the underlying case.

Focusing on this Exclusion 2.g, the court agreed with NUFIC that the exclusion applied because the damage at issue arose directly from the aerial applicator’s use of its aircraft during an aerial herbicide application.

The aerial applicator argued that the exclusion conflicted with the policy’s broad coverage grant, that the aircraft’s role was only incidental, and that Texas’s “independent proximate cause” doctrine preserved coverage. The court rejected these arguments. It emphasized that the ACGL Policy was essentially a premises liability policy, not an aircraft liability policy, making it consistent to exclude damage caused by the actual use of aircraft.

Applying the Texas Supreme Court’s three-factor test from Mid-Century Ins. Co. v. Lindsey (2010), the court found: (1) the damage stemmed from the inherent nature of the aerial applicator’s aircraft, which was designed and certified for agricultural spraying; (2) the spraying occurred within the aircraft’s “natural territorial limits” even though the herbicide left the plane before causing damage; and (3) the aircraft directly produced the harm rather than merely contributing to it. (The court clarified that the Lindsey test was not “an absolute test” but a “framework.”) Finally, the court held that the independent proximate cause doctrine did not apply because the property damage would not have occurred but for the excluded aerial application. Thus, Exclusion 2.g clearly precluded coverage for the claims as a matter of law.

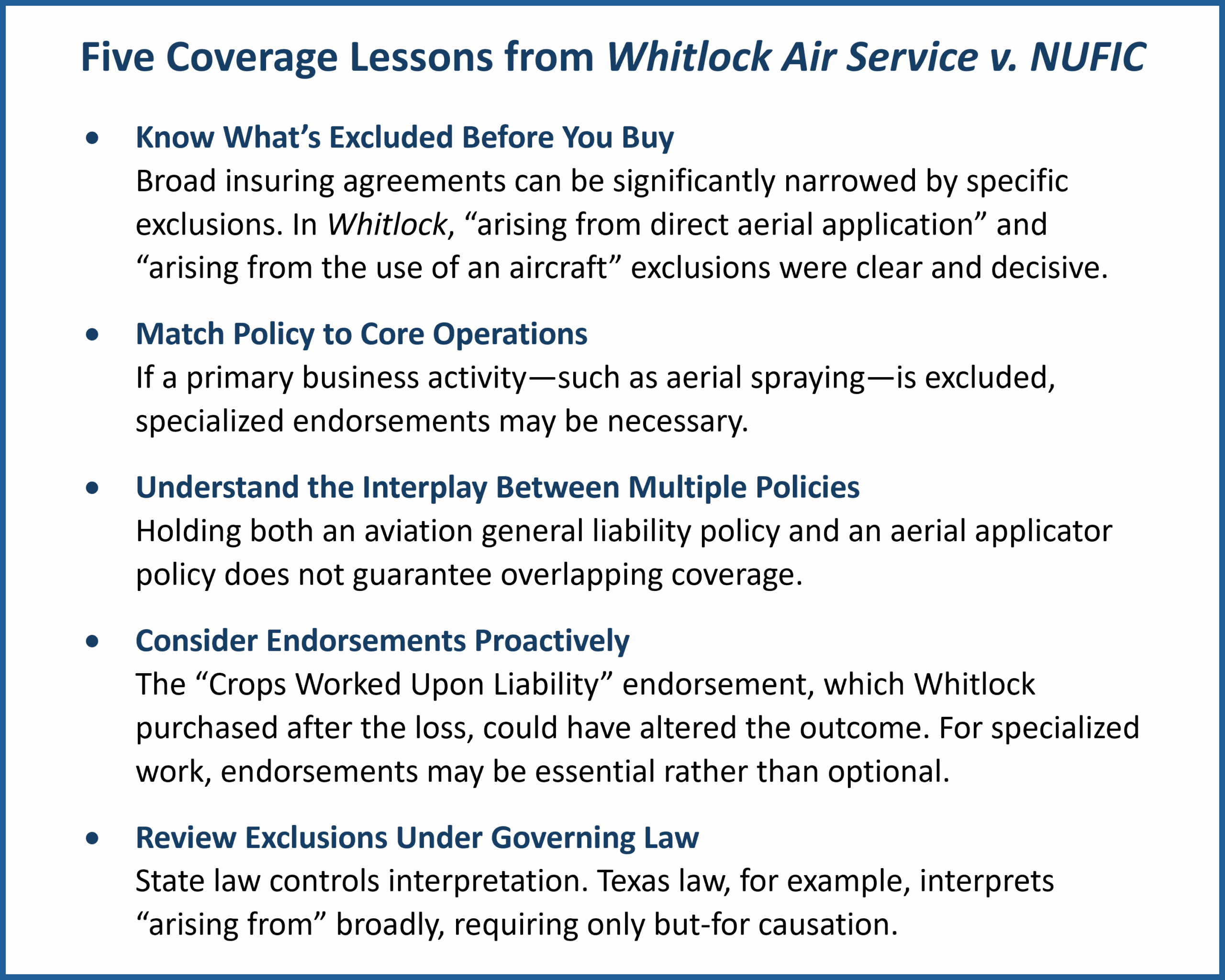

Conclusion

Whitlock Air Service showcases the importance of aligning insurance coverage with operational risks. Even where policies are valid and broadly written, explicit exclusions can remove coverage for core business activities. For aerial applicators and other specialized aviation operators, careful review of exclusionary language and consideration of endorsements—particularly those tailored to the business’s primary functions—can make the difference between having meaningful coverage and finding none available when a claim arises.

About Timothy M. Ravich

Timothy M. Ravich concentrates his practice in the areas of aviation, product, and general civil litigation. Recognized as one of only 50 lawyers qualified as a Board-Certified Expert in the area of aviation law, Tim focuses on traditional areas of aviation litigation, including product liability and airline defense, and pioneering areas such as unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) and advanced air mobility. Click here to read Tim’s full attorney biography.